Bertram Lamb Pearson

Date of birth: 1893

Date of death: 1984

Area: Wrenthorpe

Regiment: Yorkshire

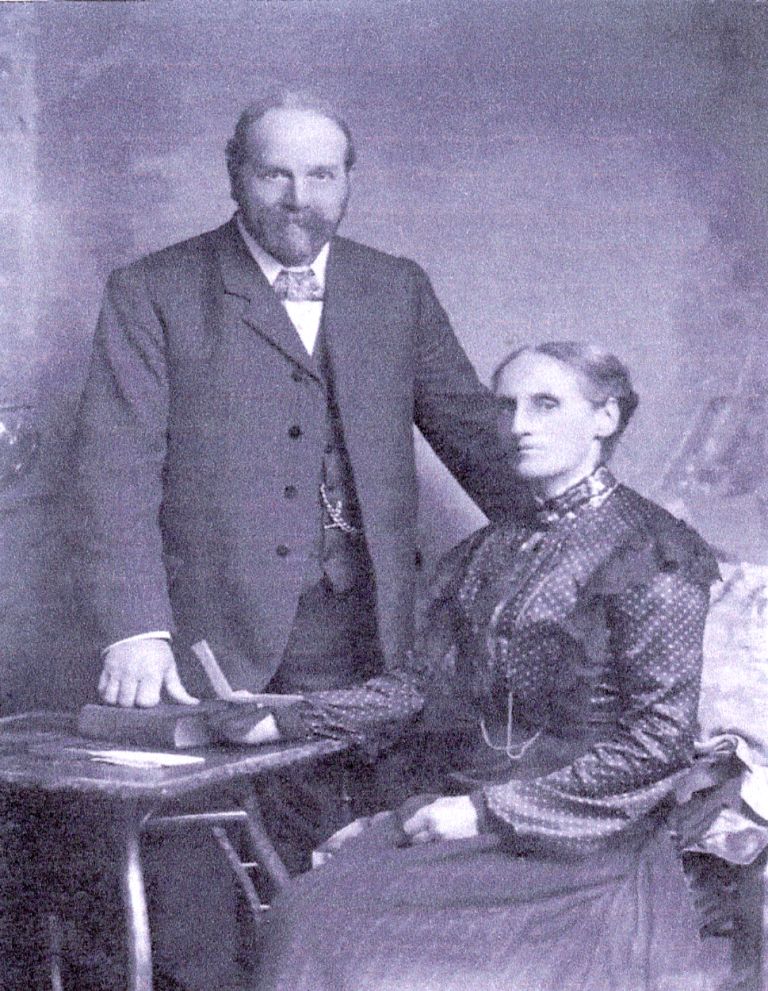

Family information: Son of William and Mary Ann Pearson nee Briggs

Rank: Captain

War Service

Bertie was a member of the Officer Training Corps, like the many undergraduates who anticipated war. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant in October 1914 and posted to the 12th Battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment. After basic training in Cottingham Park, Hull, his unit transferred to Beverley. His entire service was spent with units of what eventually became the Yorkshire Regiment, a component of the 23rd Infantry Division.

Bertie had two important strokes of luck during the Great War, neither of which looked that way at the time. The first was a blazing row with his Commanding Officer which resulted in his rustication to a service battalion. He arrived in France too late for the first murderous days of the Battle of the Somme. This did not prevent his gaining an MC for gallantry in the later stages of the battle.

The second stroke of luck was receiving three wounds at the battle of the Messine Ridge, near Ypres, in 1917. He was repatriated to the UK, and awarded the Distinguished Service Order for conspicuous gallantry. He never returned to the front and lived out the War as an instructor.

The 23rd Infantry Division took part in the early days of Passchendaele and was then assigned to the Italian front. So Bertie was one of the lucky ones. Later in life he wrote a full, but not always clear, account of his war service. Given limited space, I have chosen some quotations to give the flavour of a young officer’s life in the Great War at first hand. I have also included what he would never have done, citations for his Military Cross and DSO.

A young officer’s first day:

“I still clearly recall my first day with the 12th East Yorkshires. My Company was doing company drill in the park when I turned up and I was given command of No.15 Platoon. No one had uniform to wear and our “equipment” consisted of broomsticks instead of rifles. My Company Commander (not a regular officer) was a man who threw his weight about a lot on the parade ground. … Since I had missed OTC camp that summer, I hardly knew what a platoon was and certainly had scarcely a rudimentary idea of the new company drill. However, with the very loyal help of a Platoon Sergeant who had served in the Territorial Army, I survived.”

After his disagreement with his CO:

“The upshot of some weary weeks of waiting was that I was transferred to the Green Howards (Alexandra, Princess of Wales Own Yorkshire Regiment) and was directed to join the 13th Battalion of that Regiment – a “bantam battalion” recently formed of men who had been turned down at an earlier stage of recruitment owing to lack of inches or for some other shortcoming in the eyes of the powers-that-be. I soon found myself in a hutted camp with this unit on Cannock Chase, a dreary remote area in wartime, however attractive it may (otherwise) be.”

Bertie goes to war, posted as a Lieutenant to the 8th Yorkshires i/c ‘A’ Company:

“It was with a real thrill of happiness that I and a few other officers received instructions to go to Folkestone and proceed overseas. It was an even greater thrill to travel through northern France surrounded by evidence of real war, particularly the cattle trucks, each marked ‘Hommes quarante, chevaux huit’, and to hear real war songs like ‘I want to go home’.”

Bertie earns his first medal near Le Sars, towards the end of the Somme campaign – the citation for his MC:

‘In October when a portion of the enemy trench had been captured he consolidated, the position came under heavy bombing and shell fire and it was due to his organisation and example that three counterattacks were repulsed. The following evening when the captured trench was obliterated by heavy artillery he rallied his men, reorganised the position and inflicted further loss on the enemy. Throughout a very trying time he showed an exceptionally fine example; three of his company officers were wounded. MILITARY CROSS’.

During the course of this engagement, according to his own archive, Bertie received a signal from his Battalion commander:

‘Major Western to OC ‘A’ Company; Well done everyone. Warmest congratulations. No sandbags at present. Pull in the sides of the trench to make a bloc. Water is being sent up by Brigade. No more bombs available at present. Hold the bloc with a few bombs or Lewis gun. 1.30 a.m.’.

The 23rd Infantry Division moved from the Somme to Ploegsteert (“Plug Street”) in Belgium in late 1916. Bertie was ordered to reconnoitre the front:

“We were told that we could ride part of the way, but only on mules, as horses were too valuable to risk within shell-fire. So I went down to the transport lines to get my mule. I had never ridden a mule before and, with the help of my groom, I at last got on its back to discover to my dismay that a mule has really no forequarters and once it gets its head down, riding it is like sitting on the edge of he world. My groom had thoughtfully put in a curb bit (knowing, as I did not, the insensitivity of the of the mule’s mouth), and with great effort I managed to persuade the mule to move about 100 yards from the transport lines. There it decided it wished to go back and no pressure that I could exert with the bridle and curb and a hunting crop could prevent it from doing so. So I arrived back in the transport line, in much humiliation and to the delight of the transport men, and I decided to walk all the way to the front.”

The 23rd Division moved again, this time to the northern end of the Ypres salient, between Ypres itself and Messines.

The wait for Bertie’s next battle was both tedious and physically unpleasant:

We thus spent the winter “commuting” between the front line and Ypres – occasionally further back near Poperinge – “four days in and four days out” . The (trench)raids by both sides (mostly I think to take prisoners and so identify the units opposite), and the damage to the trenches and the loss of life which this entailed, broke the monotony. Trench discipline was strictly enforced, including daily foot inspections to see that all were using whale oil (an odorous concoction) which was supposed to prevent the onset of “trench feet”, and it was regarded as rather a black mark against one’s company if one had to send a man back with this malady. Foot inspection was normally carried out immediately the men stood down from morning “stand to” at dawn.

Bertie hated the obligation to censor his troops’ letters to wives and sweethearts. His personal archive contains a letter to his elder sister Mary (his surrogate mother), of which this is an extract, dated 17th April, 1917:

“My Dear Mary. I’m sending you some lace which I bought – I’m told at West End prices. I hope you’ll excuse certain of these ‘lingeries’ (?) as they appear to argue an undue ‘gout de connoisseur’ on my part, but really it is the fault of your sex who will put trimmings on extraordinary places – where it seldom (?) catches the eye. Anyhow, the young damsel who lifted my bawbees [took my money] said it was alright. You might send Evelyn a bit as a souvenir (if she’ll accept it) – I haven’t another box to send separately. The book of words for this curious collection of cloth reads as follows:

1 dress in …. Lace.

1 ‘set’ (ye gods!) in Bruges flowers

1 metre Valenciennes.

1 cap in Bruges lace and Valenciennes.

1 collar in Bruges flowers.

This may convey something to you – it doesn’t to me. She said it was all handmade – God only knows.

With all love.

Bertie

Before the advance to Passchendaele (a slaughter house to match the Somme as it turned out) it was necessary to clear the Germans from their vantage points along the Messine Ridge. Tunnels had been driven under the German positions and packed with explosives. I am quoting at length from Bertie’s account at this point because it was undoubtedly his ‘finest hour’. He led the attack on the ‘Caterpillar’, a long low mound of railway cutting below ‘Hill 60’:

“The actual assault took place at 3.10 a.m. on the 7th June and it was a truly weird and awesome spectacle when the mines were fired and we advanced on the enemy under huge lumps of earth and other things. These were the days when the powers that be believed in the policy of a limited offensive and my company’s job was to advance to an imaginary ‘red line’ drawn on a trench map and consolidate the position whilst the next battalion moved past us to the ‘black line’, some hundreds of yards further on and no less imaginary, and then consolidate the further gain.

In point of fact, the blowing of the mines had so demoralised the Germans in front of us that, as I myself could see, my company could have reached the ‘black line’ and some distance beyond it with little in the way of casualties: whereas the delay occasioned by the by the next battalion’s leap-frogging past us gave the Germans the chance to reorganise and bring their machine-guns into play, inflicting far heavier casualties than we had suffered. I myself got damaged in the leg and elsewhere [in fact there were two more serious bullet wounds in his shoulder] from enemy gunfire and discovered after an attack of fainting that I was being carried back from the line in a stretcher. On the way we came across a German who, like myself, had been damaged in one leg, and finding that the German and I could hobble along with one another’s help I sent the stretcher back to deal with more serious casualties [bear in mind that he had suffered three wounds!], and thus arrived at a First Aid Post. I do not know what happened to the German: but I was duly patched up and despatched to the casualty clearing station.”

The Yorkshire Post made rather more of this incident, quoting his citation. Capt. Pearson had received the DSO for conspicuous gallantry:

‘in leading his company to their objective with great skill over difficult ground. He personally killed four of the enemy and, having been wounded a second time, he lay in a shell hole giving all necessary orders until he fainted from loss of blood. He set a fine example of pluck and skilful leadership’

Lieutenant Colonel Western, Bertie’s commanding officer, described the incident somewhat differently:

‘Captain B.L. Pearson, after capturing the Caterpillar, pushed on to his objective with three wounds and a broken collarbone in spite of the expostulations of his company sergeant major, who begged him to allow himself to be taken back. It was only when he fainted from lack of blood that he was removed.’

Bertie’s personal account continues as follows:

“At Preven, where I was found lying on the ground by my Doctor brother [ Lionel; four Pearson brothers served in the Great War, two as medical officers], very dirty and dishevelled and wearing a Tommy’s uniform with my rank badges sewn on to it. (After the heavy losses on the Somme it was decided that in future officers should wear Tommies’ uniforms on going into action, so as not to be picked off so easily by the enemy, and should also carry rifles. But this latter I managed to avoid doing, since the rifle occupies one’s hands and I wanted to be free to carry my favourite offensive weapons, viz. a revolver and a hunting crop). My brother told me that I needed a bath and some food and drink and, after he had seen to this, he introduced me to his ADM, a very pleasant Canadian RAMC Colonel, who received an immediate answer to his inquiry whether I would like a spot of sick leave in England, wrote something on the casualty card tied to the top button of my jacket. Thereafter I was the subject of almost VIP treatment. I and two other officers of my Battalion who had become walking wounded travelled down to Etaples on the hospital train on which my brother had worked and, after a really delightful period in hospital in Etaples, I was put on a hospital boat, with a small cabin to myself, and travelled up from Dover to Charing Cross in a hospital train (on which I met a man who had been at Oxford with me).”

Bertie was never to return to the front, despite a year of the War remaining. He attended successive medical Boards, but on no occasion was he found fit for overseas duty. He was treated first in a military hospital in Park Lane, and then sent north to convalesce. His first medical Board report recorded ‘a shrapnel bullet lodged near the first wound’. Both wounds in his shoulder were declared severe. Bertie described his recuperation as follows:

“…I was sent to convalesce at Escrick Park near York, the home of Lady Wenlock, whose daughter, the Hon. Irene Lawley, had turned it into a convalescent home for officers with the help of a trained Sister and a number of here VAD friends. My stay there was indeed a delightful interlude, wrapped in the lap of luxury and, towards the end, filled with a round of social activities.”

I believe that he met his future wife Gladys (always known as ‘Gla’) at this time. She lived at nearby Pocklington. After uncongenial home postings, including training would-be officers, many of whom in his opinion ‘couldn’t organise a row of ducks’, it was time to be demobilised. Bertie described his last days in the Army as follows:

“When the Armistice broke out in November 1918 the whole raison d’etre of the Battalion disappeared and we became little more than entertainment officers whilst the cadets were gradually demobilised. I was naturally anxious to get demobilised myself and, on being summoned back from a few days leave just before Christmas, I felt sure it was because my “demob” papers had at last come through. Great was my anger and disappointment when I heard that I had been recalled to take the place of another officer whose papers had arrived. So I put on a mackintosh to conceal my captain’s rank badges, marched to the Brigade Office and threw my weight about with an elderly major, who in the end promised to chase up my papers. To my delight these arrived next day, duly signed up, and that evening I set off with some other lucky chaps in a brake we had hired, drawn by three horses in tandem, for Catterick Station to catch the 11.30 p.m. train for Swindon, where I had to go to be demobilised at the nearest demobilisation centre to the place where we had been mobilised, in my case Oxford. I arrived at Swindon about 6.30 a.m., got a taxi to the hutted demobilisation camp some 3 or 4 miles away, but experienced much difficulty in finding the actual office where I was to hand in my papers. At last I found, again, an elderly major in an office and again under cover of my mackintosh, threw my weight about over the inefficiency which had delayed me an hour. …… After leaving the demobilisation centre I got a taxi back to Swindon and I shall never forget the supreme sense of liberty and freedom that I enjoyed as I waited for the train to London.”

And so back to civilian life, the Civil Service and marriage.

Readers may be as surprised as I was by the relentless cheerfulness of this account of a conflict in which literally millions of Bertie’s countrymen were killed or wounded. Ninety years later, the Somme battlefield, particularly, is still a mournful place. Yet Bertie mentions killing only on rare occasions. Perhaps his story should be read as warfare recollected in tranquillity. Looking back, he remembered only what he wanted to.

Family Life

Bertram Lamb Pearson was born in Wrenthorpe, near Wakefield, in 1893. He was the youngest of ten surviving children of William Pearson and Mary Ann Briggs. His mother was the better educated of the couple and encouraged academic interests in all her children. His father was a rough and ready farmer who made money in the booming rhubarb trade of the late 19th century. The family had moved from Potovens Lane in Wrenthorpe to tumbledown Broom Hall before Bertram was born. Late in life, William built a substantial house called Fawley, which still stands on the Bradford Road.

Bertie, as he was always known, was a bright pupil whom teachers considered Oxbridge material. Like his elder brothers, he began his secondary education at Wakefield Grammar School. His studies were interrupted by a year or two at Bedford Grammar School when William retired and the family moved south for the good of Mary Ann’s health. His mother died in 1905. Bertie was 16 when his father died intestate in 1909. Most of his estate went to the eldest brother Fred, and ‘Fawley’ had to be sold. There was a move in the family to get Bertie to abandon his plans to go to Oxford, and to take an office job instead. His elder sister Mary would have none of it. She became his substitute mother, and looked after him while he finished his school career. Only then did she feel able to marry her long-time sweet heart, Jack Whitehead, and move to Hull; it was there that the Whiteheads provided Bertie with a base during his university and service careers.

Bertie justified his sister’s dedication by gaining a place at Oxford, which was to be funded by several scholarships. He entered Queens’ College in 1912. The Great War broke out just as he was about to begin his final year. He had seen this coming, and had done no study during the long vacation. It was to be the Kaiser rather than Classics for the next four years. He returned to Oxford in 1919 and, despite his absence from study and three war-wounds, took a first in Greats. He married a lady he had met during his military service. To his great sadness, the couple’s only child died in infancy. He spent the rest of his life in London as a Civil Servant at the Board, later the Ministry, of Education. He retired as a CBE and died in 1984 at the age of 91.

Roland Pearson

Bertram Lamb Pearson

Bertram Lamb Pearson

Bertie (circled) with a group of officers

Bertie (circled) with a group of officers

Bertram in middle life

Bertram in middle life

William and Mary Pearson, Bertram's parents

William and Mary Pearson, Bertram's parents