Cyril Towell

Date of birth: 1913

Date of death: 13.6.1943

Area: Brotherton

Regiment: Royal Artillery

Family information: Husband of Helen H Towell nee Black

Rank: Sergeant

Service number: 917871

War Service

The exact details of Cyril’s enlistment are not known but he was enrolled in the Royal Artillery, 125th Anti-Tank regiment service number 917871. This was a Northumbrian formed unit which was somewhat appropriate given Cyril’s family origins.

In early 1939 with war clouds gathering over Europe, it was decided to double the strength of the Territorial Army and to form a second line to the 74th Field Regiment R.A.(50th Northumbrian Division) with headquarters at Sunderland. Local men rolled along to the Drill Hall and signed on the dotted line. On the 26th August l939 the 2/74 Field Regiment R.A. set off for its first T.A. Camp at Whitby, to be recalled after barely a week.

September 1939 - war now an inescapable fact, the Unit was embodied into the Regular Army and, under the new designation of the 125th Field Regiment R.A. (23rd Division), began serious training.

The following extracts are from an account produced in a small blue book in December 1946 by the 125th Anti-Tank Regiment Relatives’ Association. The graphic story of the Regiment’s experiences was compiled by Captain Ridley and Major MacKenzie.

The account is far too long to reproduce in full so specific parts are presented to give a fair representation of the experiences that Cyril Towell would have undergone during the last 2 years or so of his life.

"Finally, in March 1941, we embarked at Gourock on the P & O liner Strathaird. Again our luck seemed to be out and after being aboard for ten days and actually sailing, we were forced to return to anchorage for repairs. These proved to be so extensive that our move overseas was cancelled pro tem. So we said good-bye to all our equipment and started all over again.

"Apparently the War Office could spare no equipment to re-fit us and so began those seemingly endless days of doing civilian jobs of fire-watching at Glasgow and later at Liverpool.

"We embarked at Avonmouth on the S.S. Oronsay and sailed about midday on 28th October 1941. As the tugs came alongside and slowly edged the ship away from the dockside our feelings were very mixed and whilst looking forward with a certain amount of excitement to our voyage, we wondered when, if ever, we would see the shores of England again. So commenced our cruise of some 20,000 miles to our ultimate destination.

This seems an inordinately long journey and members of the 125th had no idea of their final destination, if indeed their superiors did. Their journey took them across the North Atlantic to Nova Scotia, down the coast of America and back across the Southern Atlantic to Cape Town. Then up the Mozambique Channel, Mombassa and into the Indian Ocean.

"At this stage we thought we were bound for the Middle East – as in fact we were – but soon our course was altered and we were heading for India. Christmas Day was spent in the Indian Ocean and we found that turkey with all the trimmings tasted just as good eaten under tropical conditions as in a colder climate. Two days later, at about 5.30pm, Bombay was sighted through the heat haze. By 6.30pm we were anchored and saw the long, low waterfront with the Gateway to India standing out like a giant entrance to an old castle: the world famous Taj Mahal Hotel, rearing above the surrounding buildings, was shown in sharp relief.

"When they did come, our marching orders arrived suddenly and on 23rd January 1942 we were again on the docks at Bombay and embarking on the coal burning C.P.R. liner Empress of Asia. What memories the mere mention of that old hulk bring back.

"We still did not know but felt certain it must be back to the Middle East. In any case it couldn’t possibly be Malaya, the show there was virtually over, we felt certain.

"After leaving Ceylon on our port, the chart showed our course to be in a direct line for Australia. This course was kept up for a few days and then, when about 8 degrees south of the equator, it changed suddenly and we passed through the Sunda Straight dividing Sumatra and Java. Here about half the convoy left us and went into Batavia while we continued on our course heading north. At long last we knew where we were bound for - Singapore – as reinforcements. Things looked pretty grim.

"The morning of February 4th dawned with little cloud and the deep blue sea was scarcely disturbed by a single ripple. About 11am the alarm sounded and this time it was no practice. A formation of 27 Japanese bombers was flying over the convoy at a very high altitude. At first we fondly imagined that they were Allied planes but we were soon disillusioned when our escort broke convoy and commenced to zigzag. Three months had elapsed since we had heard a gun fired or a bomb explode and now, after sailing over 20,000 miles and arriving within 24 hours run of our destination, we heard again that familiar whistle. A number of bombs were dropped encircling the ship, the nearest falling into the sea within 60 yards of our starboard side.

"Apart from holing some of the lifeboats, buckling a few plates and shattering some wooden partitions, we took no harm.

"After an uneventful night the morning of the never-to-be-forgotten 5th February duly arrived. Away on the horizon, dead ahead, was a black smudge which everyone thought was a cloud – we later found that it was Singapore with a pall of black smoke hanging over it. Arrangements made for the stacking of kits and withdrawal of the remaining arms and ammunition from the armoury were progressing excellently when the warning sounded again.

"With the experience of the previous day still fresh in our minds no time was wasted and within 2 1/2 minutes everyone was at Action Stations. Again we saw a formation of 27 planes, this time travelling away from us towards the island. The warning had been given by our own ship, not by the escort vessel and after a few minutes, as nothing happened, the “all clear” was given from the bridge. Within four minutes the A.A. guns of our escort opened fire and, without waiting to hear any further warning from our own ship, everyone was back at Action Stations. This time there was no mistaking the intention of the planes. From the formation, aircraft were seen to peel off ringed by the burst of A.A. fire. The channel through which we were passing was fairly narrow and the depth of water did not allow ships of deep draughts to swing – consequently we had to carry on and hope for the best.

"At this stage the enemy bombers turned their attention to our escort H.M.S. Exeter but by skilful manoeuvring and intense A.A. fire no hits were registered and again the attack was switched to the Asia. Magazine after magazine was emptied as our men stood up to their first real encounter with the enemy – each man an example to his neighbour, but by this time the fire had got a real hold on the tinder dry woodwork and the “fiddley deck” where the guns were sited was enveloped in smoke which made it impossible to see more than a few yards. More planes came over and further bombs made hits on the ship. Meanwhile the party of volunteer stokers had proceeded to “A” deck aft amidst the wreckage of cabins and bathrooms. They ran out a hose but on turning the cock all they were able to get was a mere trickle of water. Had the circumstances not been so serious we could have appreciated the humour of the situation. If only water had been available the story might have been different, but for some unknown reason, probably the damage done below by the explosion, all pumps ceased to function from the time the first bomb landed on the ship.

"The ship was burning furiously and although the Captain did his utmost to prevent the flames from spreading by swinging as much as he dare, it soon became quite evident that unless a miracle happened the Asia would soon be burning from end to end. The bridge was burnt out and the Colonel had joined the Captain on the flying bridge, but soon even this position had to be abandoned and the senior officers who had gathered there climbed down a rope to the forward well-deck.

"The relief of getting off the flaming ship blotted out to a large extent any sentimental feelings we may have had about being compelled to leave behind our equipment and personal belongings, some of which we could never replace. When we landed we were a sorry sight – some without shirts, some without shorts and the majority without footwear. The following morning about 60 men were still missing, but by the following day, late in the afternoon, we were in a position to account for everyone. Our only death was Lieut R B Wilson, but about 62% of the personnel of the Regiment were suffering from burns and wounds which kept the Medical Officer, his orderly and his driver busy for many hours.

"On the morning of the 8th February a message arrived from Divisional Headquarters which read:-

FOLLOWING FROM HMS DANAE BEGINS STOP FROM THE ACCOUNTS I HAVE RECEIVED FROM VARIOUS OFFICERS THE TENACITY AND STEADINESS OF THE MILITARY OF THE EMPRESS OF ASIA IS WORTHY OF THE HIGHEST PRAISE STOP ENDS GOC MALAYA AND DIVISION CONGRATULATE ALL RANKS ON THEIR SOLDIERLY CONDUCT

"Eventually we moved into the line – A. and C. Batteries and R.H.Q. to Serangoon on the 9th February. Here patrols off the coast of Johore in darkness were not very pleasant. As we had no equipment we were acting as Infantry. H Troop was the only exception, being the proud possessors of four anti-tank guns. The story of the battle for Singapore was not a long one as far as we were concerned. The campaign was practically lost before we left India. The enemy made a landing on the island on the night of the 7/8th with, it was thought, one Division and one Brigade strength. Their main drive was towards the reservoirs from the West coast. "Reinforcements had been drafted towards the Western front, but apparently they were unable to stem the attack as the enemy literally poured fresh men into the drive. Everywhere there was lack of information and fifth column work of unbelievable proportions. All that remained of the Air Force when we arrived was about nine Brewster Buffaloes which were quite useless. It appeared that their instructions were to get off the ground and keep clear when the enemy came over. On the evening of Tuesday February 10th all planes and the remaining personnel from the Air Force left the island.

"By the morning of that ill-fated 15th February we were being shelled from almost every angle except dead in rear which was the centre of the town. The enemy actually had an observation balloon up for about three hours and owing to our lack of aircraft we were powerless to do anything about it. About 3.0 p.m. the Colonel arrived at R.H.Q. with news which at first we just couldn’t believe. We knew the position was grave and that the water supply had been cut but – surrender – the very idea had never entered our heads. However, it was only too true and, acting according to orders, the ceasefire sounded at 4.0 p.m., although the enemy were still dropping bombs on the town as late as 6.45 p.m.

"After the initial shock of receiving this humiliating order the Colonel was bombarded with questions and it appeared that the main reasons that had induced the G.O.C. to capitulate were:

1. Lack of artillery ammunition, there wasn’t 100 rounds per gun left. In many cases only five rounds per gun remained.

2. The enemy had possession of the reservoirs and had cut the water supply to the town. In a tropical country it can easily be imagined what the ultimate result of this step would be.

3. An ultimatum had been given by the enemy that unless there was unconditional surrender, every European on the island would be annihilated. (The authorities knew from experiences up-country that this was no idle threat).

"That evening as we sat talking everything seemed very strange and unreal. Hushed was the never ending shriek and scream and banging of artillery fire: now all was deathly quiet. Here and there could be seen the odd light from some un-screened window and all around the sky was red with the glow from fires burning in the city. No one spoke, everyone was too busy with his own thoughts, wondering what the morning would bring. We had heard from Captain McNamara of the Police (who had been attached to us for the battle) how the Japanese treated their prisoners up country and the prospect was far from rosy. The following day was one of further suspense. At 8.0 a.m. the Japanese Army marched into Singapore and the flag of the Rising Sun was hoisted over the Government buildings. We were, however, left pretty much to ourselves during that day.

"On the 17th we marched to Changi, some 20 miles from the centre of the city and commenced our 3 ½ year captivity. In olden days the experiences that followed might have formed the inspiration for a huge tapestry, the main motif inevitably of dark and sombre hue, but running through the entire pattern a continuous golden thread of the firmest comradeship and unquenchable cheerfulness.

"Easter Day 1942 saw a steady stream of men, just as dawn was breaking, heading for the rice hut. At that time there was no padre in the camp, but Major Wylie was fortunately able to step into the breach and under the most primitive conditions, in semi darkness and surrounded by bags of rice, Holy Communion was celebrated. As the early morning light filtered into the hut one could see that, in addition to our own men, the congregation included troops from almost every part of the world – Canada, India, Malaya, New Zealand etc.

"Soon after our arrival at River Valley we were put to work and for most of the time we were in Singapore we helped to clear up the debris, pushing handcarts about from point to point loaded with sand and bricks. Officers at this stage were not forced to work and usually they went out with the working parties and acted as “buffers” between the Japanese guards and the men. The Japanese took a delight in attempting to belittle us in the sight of the native population – little did they know that those natives, and we ourselves, were smiling inwardly at what was taking place under the very noses of our guards. Sgt Oag, our Regimental Armourer, who was the son of an Armourer, was quietly working in camp repairing arms for the Chinese underground organisation. Hundreds of rifles and revolvers and at least three L.M.G.’s were serviced and returned safely. All these weapons were smuggled into camp in various ways and after the necessary repairs had been completed were pushed under the wire at night. This was all Sgt Oag’s own work and for quite a time even men living quite close to him were unaware of the dangerous work he was performing.

"During August rumours were rife that all prisoners were to be taken off the island and sent up-country or to Japan. A small party had already left for Siam and soon all senior officers above the rank of Lieu-Colonel were sent overseas.

"We continued at work in Singapore until, in September 1942, we were left with only twelve officers and 240 men from the original 25 officers and 400 men who had arrived at River Valley in April. The rest had been evacuated to Changi as being too sick to work.

"For the first few months the POW's at Changi were allowed to do as they wished with little interference from the Japanese. There was just enough food and medicine provided and, to begin with, the Japanese seemed indifferent to what the POW’s did at Changi. Concerts were organised, quizzes, sporting events etc. The camp was organised into battalions, regiments etc and meticulous military discipline was maintained. However, by Easter 1942, the attitude of the Japanese had changed. They organised work parties to repair the damaged docks in Singapore and food and medicine became scarce. More pointedly, the Japanese made it clear that they had not signed the Geneva Convention and that they ran the camp as they saw fit.

"The mood of the Japanese changed for the worst when a POW tried to escape. The attempt was a failure and the Japanese demanded that everyone in the camp sign a document declaring that they would not attempt to escape. This was refused. As a result, 20,000 POW’s were herded onto a barrack square and told that they would remain there until the order was given to sign the document. When this did not get the desired result, a group of POW’s was marched to the local beach and shot. Despite this, no-one signed the document. Only when the men were threatened by an epidemic, was the order given that the document should be signed. However, the commanding officer made it clear that the document was non-binding as it had been signed under duress. He also knew that his men desperately needed the medicine that the Japanese would have withheld if the document had not been signed. But this episode marked a point of no-return for the POWs at Changi. This episode is described below.

"One incident that happened at this period of our captivity we feel we ought to mention as being typical of the mentality of the inhuman enemy who had us in their power. At the end of August 1942 Colonel Fukue, the Japanese commander, called up every prisoner of war in Singapore, irrespective of rank, to sign a certificate that he would not attempt to escape.

EVERY MAN REFUSED TO SIGN. As a result on 2nd September the Jap commander ordered all ranks (except those sick in hospital) to proceed to Selerang. The barracks at this place consisted of blocks of buildings forming three sides of a rectangle with an asphalt square in the centre. In peace time the maximum accommodation was for 850 men. Into the square and the surrounding buildings the Japs squeezed approximately 16,000 men.

"It was late evening before the final party arrived. There were no sanitary arrangements and it was imperative that something drastic be done immediately. No time was lost and by the aid of the flickering light from oil lamps men worked all that night digging deep trenches all over the square. The cheerful spirit in which they carried on their job seemed to annoy our hosts. Rations (which were scarce) were cut and the water supply was barely sufficient for drinking purposes. There was not room for everyone to lie down under cover of the buildings and all kinds of contraptions were erected where possible in the square to provide cover from rain and sun.

"After the first day threats were made to cut still further the supply of both rations and water. Within 48 hours cases of dysentery etc were reported and the sick men were taken to an improvised shelter, used as a makeshift hospital, to await transportation to Changi. The Senior Officers were in consultation almost continuously, but it was soon apparent that the Japs were determined to have their own way. They made a further threat that unless we signed soon all the patients from Changi Hospital would be moved to Selerang to swell the already hopelessly overcrowded army of men pent up in the restricted area.

"The train journey into Siam was a veritable nightmare. With an average of 32 men packed into a steel truck the going was pretty grim to say the least. We soon found that for anyone to get even a suggestion of rest we must adopt some workable system. In the majority of cases this was accomplished by half the men standing close together at one end of the truck whilst the remainder lay curled up on the floor. After a reasonable period the position was reversed so that every man got his turn to lie down. The heat was intense and many of us remember yet the relief we felt when at one of the stops we were able to stand for a few moments under the outlet of a locomotive water tank by the side of the railway. What a Godsend were those Red Cross supplies we had got before leaving during those four nights and three days on that ghastly journey.

"The landscape altered little until we crossed the border at Padang Besar. Up til then there had been the eternal rubber plantations, coconut palms and rugged high ground in the distance but, once past the frontier, the rubber plantations gradually decreased and were replaced by paddy-fields which increased until after a few miles inside the border they stretched as far as the eye could see. We arrived at Ban Pong on the morning of 18th October and were marched to a staging camp. After a rest our trek into the interior commenced. Early parties marched the whole distance to Tonchan by way of Kanburi and then through the jungle. Later parties had the help of transport as far as Kanburi.

"Tropical rain, tropical diseases, little food and less medical supplies, with hard work the whole time interspersed with regular beatings-up, made life very difficult. One could easily fill a book on our experiences and the incidents of those days, but the majority of those incidents are perhaps best treated as a bad dream which we want to do our best to forget. Mingled with the daily round of hard work there was, however, that unconquerable never failing sense of humour so typical of the Britisher, even under the very worst of conditions. S’truth it was only that indomitable spirit that kept us sane. In the early days we remember a working party of 25 men parading under a Korean guard in two ranks and proceeding to number off: 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, Jack, Queen, King, to which the Korean replied with a perfectly straight face “O.K. March.” Later we were ordered to number off in Japanese.

"The Burma-Siam Railway, previously surveyed by both British and German engineers and in each case turned down as being too expensive in the inevitable loss of man-power, was slowly growing under the harsh drive of the Japanese. The Regiment was spread in groups along the whole length of the proposed railway in Siam from Chungkai to Niki. The Japanese orders were that, irrespective of any conditions whatsoever, the railway MUST be completed by a certain date. That date was rapidly drawing near and in true Japanese fashion the guards and the engineers strove to carry out their orders even though men were dropping dead at work. Every few minutes the command “Speedo Speed Bugaro” would be screamed by one or more irate Jap and more often than not the command was accompanied by a lash from bamboo rods. Is it to be wondered at that our treatment during those ghastly months did not tend to improve the love we had for our temporary masters?

"In one camp of 1,500 men, where a small contingent of our boys was working, after three months there remained only one officer and five men fit to go out to work. Officers were compelled to work about February 1943 and at one time a party of some 300 officers was brought from Changi supposedly for a rest and change of air and put straight onto railway work and felling trees.

"By November 1943 the railway was through and a few months later those of us who remained were gradually sent down-river and congregated at base camps in the Tamuang, Kanburi, Chunkai area."

By the time the railway was finished, however, Cyril Towell was dead. He succumbed on the 13th June 1943 at the age of 30.

We also know that at some stage Cyril was mentioned in Despatches. The Mention in Despatches (M.I.D.) for a Soldier is not an award of a medal, but is a commendation of an act of gallantry or service. Cyril Towell’s name would appear in the official report written by a Superior Officer and sent to the high command, in which is described the Soldier's gallant or meritorious action in the face of the enemy. Given the above account it is likely this meritorious action took place on the ship Empress of Asia. Although no account is given of the ‘meritorious action’, like all MID’s, it was published in The London Gazette, Supplement 37671, Page 3919 on the 30th August 1946.

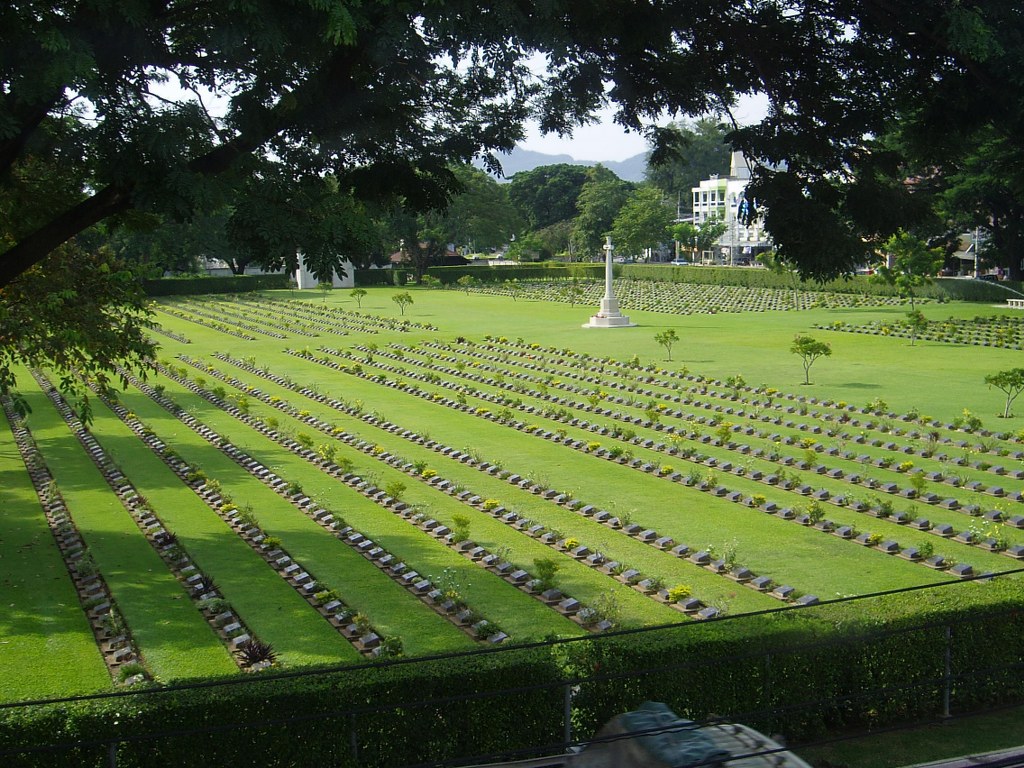

Cyril Towell was buried in the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery.

The building of the so called ‘Death Railway’ was the subject of one of the most famous of all WW2 films - Bridge Over the River Kwai starring Alec Guinness.

Family Life

Cyril was the middle of the three Towell brothers and also the second of the three to be killed in WW2. The main part of the family history details are in the account of Harold Towell who was the eldest of the three.

Cyril married Helen H Black in Sunderland during the last quarter of 1939. This would indicate that he was already in the army as his regiment was Northumbrian based.

Their son Anthony N Towell was born during the first quarter of 1941 so it is likely that he had a very brief relationship with Cyril but one he would be unable to remember.

At some stage during the war period Helen and her son moved to South Croyden.

Kanchanaburi War Cemetery

Kanchanaburi War Cemetery